I kind of forgot that I was already 65 % done with this translation when I went on my bikepacking trip from Okinawa to Nagasaki. But I’m back now, so no excuses for further delays. This the last part of Suzuki’s musings and covers the particularly notorious part about Takahata “killing” Yoshifumi Kondō.

An additional note: I wrote that the original article was posted on bunshun.jp which was not wrong, but it was originally published in the Ghibli Textbook #19: The Tale of Princess Kaguya. I have added this information to the previous articles.

Part 1 | Part 2

The original Japanese article can be found here.

“Even After Takahata-san’s Death, the Tension Does Not Subside” – Toshio Suzuki talks about Isao Takahata (Part 3)

When will this film be completed, when will it be released to the world? I didn‘t even think about that once. Let’s just release it once it’s finished. With that way of thinking, I prepared myself for the worst, including the budget. Having enough of distressing over meeting deadlines was also a reason, and I also felt like I should let Takahata do until he was satisfied. As a result, [the production] took eight years and, with a budget of 50 billion yen, became the most expensive Japanese movie in history, but I decided to not let it bother me at all.

“The Idea of Releasing ’Princess Kaguya’ and ’The Wind Rises’ Simultaneously”

But still, when I heard that the completion was in sight, I felt excitement – because Nishimura talked about summer 2013, the same timing as “The Wind Rises”. That’s when I came up with the idea of a simultaneous release. Two maestros with a teacher-student relationship and a lifelong rivalry, pitting their works against each other 25 years after “My Neighbor Totoro” and “Grave of the Fireflies” – if that came to be, making big headlines would be easy. And personally, I was also interested which film would attract more visitors and how different the critical reception would be if released at the same time.

That’s when I went to Takahata-san and explained my plan to him. But Takahata-san was not thrilled. “You want to release this film by stirring up a fire like that?” “Exactly. You see, the film cost a lot of money, and recovering the money by getting people to see the movie is one of my reasons,” I replied, but Takahata-san said he would not agree to that. At one point, Takahata-san likened my way of promotion to propaganda and become quite critical.

As a result, progress on “Kaguya” got delayed once more, and the release was stretched out until November. Admittedly, my dreams of a simultaneous release were shattered, but I thought, if it’s not meant to be, that’s also fine. In that way, I countered his stubbornness with my own stubbornness. I decided to take this contest of endurance to the limit.

Dispute Over a Tagline

When it came to the promotion, we also argued over the tagline. The line I came up with was “The sin of a princess and her punishment”. That was also written in the project proposal Takahata-san had submitted at the beginning, and anyway, it was the theme of the original story. I thought this was the only fitting line. But when I showed it to Takahata-san, his face changed colors again. Seemingly not pleased, he told me: “It’s true, initially I also thought like that. But I decided to drop that theme.”

In regard to the tagline, Takahata maintained a peculiarly consistent stance. “We shouldn’t evoke a wrong impression of the work,” he said. To explain this further, he wanted to make “sin and punishment” the theme of the work, but was unable to realize it in practice, which was why that tagline was wrong.

In regard to the tagline, Takahata maintained a peculiarly consistent stance. “We shouldn’t evoke a wrong impression of the work,” he said. To explain this further, he wanted to make “sin and punishment” the theme of the work, but was unable to realize it in practice, which was why that tagline was wrong.

After he told me this, I had no choice but to think of a new tagline proposal. He acknowledged that this time, the content wasn’t misleading, but the uneasy feeling I had did not subside. “I very well understand that this tagline would be less problematic, but the ’sin and punishment’ tagline was much better received by the [production committee] [lit.: parties involved],” it slipped out of my mouth. It was then that Takahata-san sullenly retorted: “I see. I don’t care anymore. Do what you want.”

“Shouting Over a Poster”

We then used “sin and punishment” and made the first poster, but that lead to yet another clash. For the test print run, we made one version with colors true to the actual key frames, and one version with a fluorescent pink that was a little flashier. I took those to Takahata who looked at the flashy one and lost his temper. “You seriously want to sell this work like that?!” While he was shouting furiously, I remained silent and Kazuo Oga-san who had drawn that picture happened to pass by. Surely Takahata thought he would be on his side. “Oga-san, what do you think?” I asked him. At that moment, our eyes met for a second. Thereupon, Oga-san replied: “I think this one is better” while pointing at the flashier one. I’m sure that must have been bitter for Takahata-san.

But that issue had an even more lasting effect. After that, when the production was in a late stage, Takahata-san said: “Because of your tagline, I don’t know what to do.” Nowadays, even the promotional tagline is subconsciously influencing the viewers who visit the cinema. Based on that, the tagline “The sin of a princess and her punishment” shouldn’t be mentioned in regard to the movie. I felt it was inevitable, so I decided to add a quote [from the movie]. “Please remember that,” he emphasized. Then, every time when he was giving interviews, he kept saying: “This tagline is wrong.”

In other words, the movie “The Tale of Princess Kaguya” was a struggle between Takahata-san and me. That’s why I couldn’t just calmly watch the movie. But when it was completed, the one thing that I frankly must admit was amazing was how he captured Princess Kaguya as a woman. Including the scene of her first menstruation, she was portrayed as a woman perfectly. There are no other directors who can do that. I’ve got to hand that to him. I really think the movie turned out well.

“Takahata-san Was Trying to Kill Me”

Every human does good and bad things in their lives, and due to their work, movie directors can’t always be good people. There are times when they involuntarily change the lives of others, and sometimes become the target of resentment. In Takahata’s case specifically, making good movies meant everything to him to the point where everything else was secondary. You could very well call it “work supremacism”. But there’s no denying that this destroyed a lot of people.

Kondō Yoshifumi, the animation director of “Grave of the Fireflies”, was one of these people. When he visited Sendai for the promotional campaign of his first and last movie as a director, “Whisper of the Heart”, he talked to me about Takahata-san that night and couldn’t stop. “Takahata-san tried to kill me. When I think of him, even now my body starts to shake.” Talking like that, he cried for two hours. After that, he fell ill and died at the age of 47. While we were waiting for his bones to be burned at the crematory, S-san, an animator and colleague who had worked with Takahata and Miyazaki since their times at Toei Dōga, said the following: “It was Paku-san who killed Kon-chan, wasn’t it?” The air froze instantly. After a little while, Takahata-san silently nodded.

“The Man Isao Takahata” as Told by Hayao Miyazaki

If it was for the sake of a work, he did everything. As a result, he wrecked the people we had pinned our hopes on one by one. Miya-san often said: “The only staff member who survived Takahata-san was me.” This is no exaggeration; it is the truth. You may think working under Takahata will be a good learning experience – but it’s not as simple as that. You have to be prepared to be exploited, overworked until you break.

“Paku-san” is the god of thunder.” That’s what Miya-san said a lot recently. When Takahata-san got angry, he was always serious. He doesn’t get angry to discipline someone or change their attitude towards work. And because he’s serious when he gets angry, he knows no mercy. He doesn’t leave a way to escape and doesn’t extend a helping hand afterwards. That’s what makes it so scary.

“Paku-san” is the god of thunder.” That’s what Miya-san said a lot recently. When Takahata-san got angry, he was always serious. He doesn’t get angry to discipline someone or change their attitude towards work. And because he’s serious when he gets angry, he knows no mercy. He doesn’t leave a way to escape and doesn’t extend a helping hand afterwards. That’s what makes it so scary.

As Nitta Hiroshi from Shinchōsha who was involved in the production of “Grave of Fireflies” fittingly said: “Matsumoto Seichō, Shibata Renzaburō, Abe Kōbō – I have worked with many writers, but never encountered a person like [Takahata-san]. Compared to Takahata-san, they all seem normal.”

I have also met all kinds of people, but no one else like Takahata-san. No matter what the staff did for him, he never expressed gratitude. According to his way of thinking, since they were working together on something, it would have been strange for him as the director to express his gratitude. That might seem logical, but from an interpersonal perspective, he lacked feelings – his was a destructive way of thinking.

“You alone tried to bring Paku-san to make movies. No one wanted that,” Miya-san once said to me. But during the production of “Heidi, Girl of the Alps”, Miya-san himself went all the way to Takahata-san’s place every day to urge him, who had no intention to so, to work. Going even further back in time, during the times of Toei Dōga, animation director Ōtsuka Yasuo-san insisted: “If you don’t let Takahata direct, I’m not doing it,” which let to Takahata’s directorial debut on “Hols, Prince of the Sun”.

“Even After His Death, the Tension Does Not Subside”

Looking back, there was no work Takahata said he really wanted to make on his own accord. But still, myself included, the people flocked around him and pushed him to make [movies]. Was that the reason for his talent? I don’t really understand it myself.

To begin with, no matter if writer or movie director, people who want to create something to show it to others usually have a strong desire for recognition, right? I believe Takahata also had this desire. But at the same time, in accordance with his destructionalism (destructive principles / 破滅主義), I have the feeling he was also tormented by self-destructive desires. I think the person Takahata Isao can be described as in a rift between these two tendencies.

There is this word called “charisma” – people are deeply shocked [by someone], think that there is something to that person and start following them. This is neither good nor bad. But once captivated by this charm, it doesn’t let them go until that person dies. No, even then it doesn’t end.

That’s why even after working with Takahata-san for 40 years, I couldn’t let my guard down even once. Even after his death, this tension does not subside. That’s how I feel. Expressed in more beautiful words, you could say he still lives on in my heart. But that’s not what it is. I want him to peacefully leave this world behind, but he simply won’t do that. What is this feeling? What was there to this person? Me and Miya-san, we want to find this answer, and continue our wake together even after his death.

By the way, in the movie Miya-san is currently working on, “How Do You Live?” (Kimitachi wa Dō Ikiru ka), there is a character modelled after Takahata-san. I’m interested in how Miya-san will handle this character. After Takahata-san’s death, the progress on the storyboards that went smoothly has halted now for two months. That’s why even now I don’t feel like praying for Takahata’s happiness in the next world. That might be difficult to understand for outsiders. But these are my genuine feelings right now.

That’s it for now, thank you for reading. I personally find Suzuki’s stories very fascinating. Studio Ghibli is not bound by any higher entity trying to protect a brand image or anything, so Suzuki, Miyazaki and Takahata were always talking very freely about basically anything – quite unlike what Japanese usually do. The amount of documentation of Studio Ghibli works, their productions and the people involved is insane. For me that is a big part of the fascination, and the deeper I delve into it, the more engrossing it becomes. Miyazaki, Takahata, Suzuki – it’s not only their works, I also find their personalities highly interesting.

There are other magazine article translations I’m planning to do – one very recent article in the same style where Suzuki talks about Miyazaki (references by ANN here), the work on Spirited Away and the footprint Miyazaki left on the Heisei era. Another very interesting article from 1963 was re-published yesterday – it’s about legendary animator Reiko Okuyama who was one of the first woman to enter the animation industry in Japan. She is the model for the current NHK morning drama (asadora), Natsuzora, that tells the story of a girl growing up after World War II and eventually entering the animation industry. In the article, she talks about her experiences as a woman in a work environment dominated by men and why she decided to become an animator.

If you have any interesting suggestions for articles that still need translation, feel free to mention them in the comments.

The third reason was that Takahata was so into studying that when something caught his interest, he wouldn’t stop researching until he was fully satisfied. This was a common reason for delays in his works. For example, the famous dyer’s safflower picking scene in Only Yesterday (pictured on the right) took more than a month.

The third reason was that Takahata was so into studying that when something caught his interest, he wouldn’t stop researching until he was fully satisfied. This was a common reason for delays in his works. For example, the famous dyer’s safflower picking scene in Only Yesterday (pictured on the right) took more than a month.

Here I also found messages from various notable Japanese personalities, including the late Ghibli director Isao Takahata, producer Toshio Suzuki, composer Joe Hisaishi, In This Corner of the World director Sunao Katabuchi, mangaka Fumiyo Kōno, composer kotringo. I was amazed how many of these names were familiar to me.

Here I also found messages from various notable Japanese personalities, including the late Ghibli director Isao Takahata, producer Toshio Suzuki, composer Joe Hisaishi, In This Corner of the World director Sunao Katabuchi, mangaka Fumiyo Kōno, composer kotringo. I was amazed how many of these names were familiar to me.

Miyazawa’s most famous work is without doubt Night on the Galactic Railroad, a story about two boys, Giovanni and Campanella, who travel through the galaxy in a train before their inevitable parting. The story begins at Tanabata, the Star Festival in July. Giovanni boards a train that magically appears when he climbs a hill alone at night and meets his best friend, Campanella, there. What he does not know yet is that Campanella had fallen into a river that night, losing his live. The mysterious train takes them on a journey through the galaxy. The two boys witness all kinds of wondrous phenomenons, see beautiful places and meet bizarre people. They talk about their loved ones and the true meaning of happiness. But Giovanni is not dead, so he has to return to Earth in the end, while Campanella continues his journey into the next world.

Miyazawa’s most famous work is without doubt Night on the Galactic Railroad, a story about two boys, Giovanni and Campanella, who travel through the galaxy in a train before their inevitable parting. The story begins at Tanabata, the Star Festival in July. Giovanni boards a train that magically appears when he climbs a hill alone at night and meets his best friend, Campanella, there. What he does not know yet is that Campanella had fallen into a river that night, losing his live. The mysterious train takes them on a journey through the galaxy. The two boys witness all kinds of wondrous phenomenons, see beautiful places and meet bizarre people. They talk about their loved ones and the true meaning of happiness. But Giovanni is not dead, so he has to return to Earth in the end, while Campanella continues his journey into the next world.

urthermore, I found the following English picture books of Miyazawa works in the souvenir shop of the Kenji Miyazawa Memorial Museum:

urthermore, I found the following English picture books of Miyazawa works in the souvenir shop of the Kenji Miyazawa Memorial Museum:

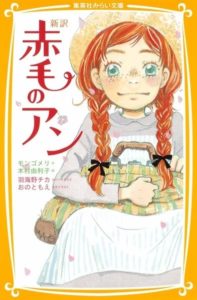

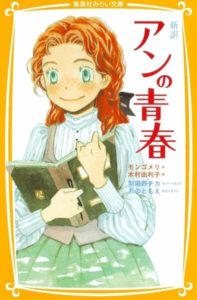

Umino says, she read Anne of Green Gables and Heidi as a child, so she was very happy when she was asked the draw the new cover artworks for Anne. She is very fond of the recent adaption Anne with an E (

Umino says, she read Anne of Green Gables and Heidi as a child, so she was very happy when she was asked the draw the new cover artworks for Anne. She is very fond of the recent adaption Anne with an E ( Umino says, she is the kind of reader who rereads the same book many times. As a child, Anne of Green Gables, Heidi and the Little House on the Prairie book series were the ones she read over and over again, starting from her first elementary school years.

Umino says, she is the kind of reader who rereads the same book many times. As a child, Anne of Green Gables, Heidi and the Little House on the Prairie book series were the ones she read over and over again, starting from her first elementary school years. Reading the meal scenes in Anne inspired similar moments in her manga: “Because I read these scenes so passionately, I thought having meal scenes in my own manga would make it more fun for the readers.” Getting letters and photos from readers who tried to cook soft-boiled eggs the way they remembered it from March comes in like a lion made her very happy.

Reading the meal scenes in Anne inspired similar moments in her manga: “Because I read these scenes so passionately, I thought having meal scenes in my own manga would make it more fun for the readers.” Getting letters and photos from readers who tried to cook soft-boiled eggs the way they remembered it from March comes in like a lion made her very happy.

In regard to the tagline, Takahata maintained a peculiarly consistent stance. “We shouldn’t evoke a wrong impression of the work,” he said. To explain this further, he wanted to make “sin and punishment” the theme of the work, but was unable to realize it in practice, which was why that tagline was wrong.

In regard to the tagline, Takahata maintained a peculiarly consistent stance. “We shouldn’t evoke a wrong impression of the work,” he said. To explain this further, he wanted to make “sin and punishment” the theme of the work, but was unable to realize it in practice, which was why that tagline was wrong. “Paku-san” is the

“Paku-san” is the