This is the second out of three planned post about Kenji Miyazawa.

1) The Life, Works and Themes of Kenji Miyazawa

2) Kenji Miyazawa in Anime and Manga: Adaptions and Influence

3) A Trip to Kenji Miyazawa’s Beautiful Hometown Hanamaki

Kenji Miyazawa’s stories became very popular in post-war Japan, so naturally there have there have been animated adaptions. The earliest ones were puppet animations – The Restaurant of Many Orders (1958) and Gauche the Cellist (1963) – and the most recent adaption is Matasaburō of the Wind from the Anime Mirai 2016 (Young Animators Training Program).

But Miyazawa’s influence goes far beyond just adaptions of his work. His ideas had and continue to have a big impact on generations of artists. The most notable case may be Leiji Matsumoto’s works, particularly Galaxy Express 999 and The Galaxy Railways.

In this article, I will try to provide a non-exhaustive overview of these adaptions and influenced works.

Adaptions and Re-Adaptions

Take a short glimpse at the anime works that credit Kenji Miyazawa and you will notice: Many of them have been adapted two or even three times. Out of the huge catalogue of Miyazawa short stories, a few seem to me particularly popular. Gauche the Cellist, Night on the Galactic Railroad, Matasaburō of the Wind and The Life of Budori Guskō have all been adapted twice or three times even over the course of the decades.

Out of the ones I have seen, all had an interesting artistic directions. There are more straightforward works, like Takahata’s take on Gauche, but the majority of the adaptions have unusual – sometimes daring and experimental – visual styles that complement the eerier, weirder elements in Miyazawa’s stories. Unfortunately, some of the older works are hard to get your hands on nowadays – I’m not sure all of them were released physically in the first place.

Let’s take a short look at the works by the most prestigious directors.

Isao Takahata’s Cellist

Takahata’s 1982 adaption of Gauche the Cellist may seem fairly conventional. It adds a few details to the original story, but nothing major. However, this was an independently produced endeavor with great attention to detail that took 6 years to complete and was the beginning of an approach to anime production that Takahata would later use again in My Neighbors the Yamadas and The Tale of Princess Kaguya: To attain the highest level of artistic consistency, the 63-minute movie was solo-layouted and key animated by Yoshitsugu Saida.

Most of the movie is fairly realistic – the lavish backgrounds stand out in particular – but there are some very stylized scenes of comic relief that may surprise people who only know Takahata’s newer works. One scene also pays tribute to Tom & Jerry.

Also notable is the attention payed to the music. In addition to the pieces used in the original story, Takahata chose a few classical compositions for the movie. Saida took cello lessons in order to animate the movements as accurately as possible. The song Hoshimeguri no Uta written by Miyazawa himself is notably used in the opening credits.

While other adaptions of Miyazawa works may stand out as more artistically daring, this is definitely an excellent adaption of Gauche. I have to admit the original story never resonated much with me, but any admirer of animation as an art form should watch Takahata’s Gauche at least once.

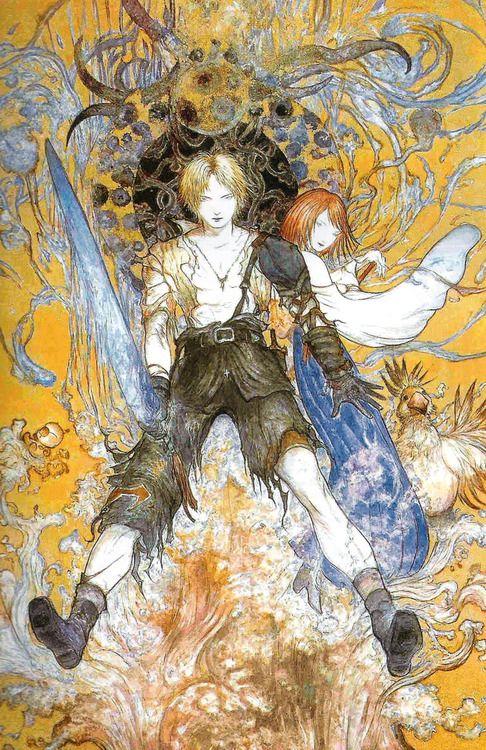

Gisaburō Sugii’s Cats in Space

Gisaburō Sugii, one of the earliest directors in TV animation, took on the arguably most famous animated Kenji Miyazawa adaption, released in 1985: Night on the Galactic Railroad. In the beginning, Sugii had trouble adapting Miyazawa’s abstract work into something concrete, as Jonathan Clements describes, so he made an interesting choice: “It was the manga artist Hiroshi Masumura who came up with a solution – keeping the original abstraction in the anime by making the lead characters cats.”

The original work was already quite weird at times, but Sugii’s version takes it to a new level. The movie is dark, slow and sometimes outright creepy. It still keeps Miyazawa’s message intact, but it’s nothing I would show to children as casual entertainment. That being said, the very nature of this highly unique movie and its incredibly strange atmosphere make it quite compelling. Definitely recommended!

Funny anecdote: The movie was recently licensed in Germany by publisher Anime House, but the voice and music tracks were lost over the years, so in order to produce a dubbed version, Anime House had to recreate these tracks. They used the official soundtrack release to restore the music and the sound effects while the missing parts of music were recreated from scratch by the dubbing studio, based on the original sound. The process was documented here.

I’m personally more fond of Sugii’s take on The Life of Budori Guskō 27 years later (the second time the story was adapted in animated form). The movie also portrays the main characters as cats and has much of the same eerie weirdness as Sugii’s Railroad, but I found it more tangible and the visuals more appealing. The story also shares some biographical elements with Spring and Chaos (see below). For more details on the production process, read Clements’ article linked above.

(Screenshots from sevengamer.de)

There’s another “adaption” of Night on the Galactic Railroad with the English subtitle Fantasy Railroad in the Stars by digital artist Kagaya – a 48-minute tribute to the story. It shows the train on its journey through the galaxy – and it’s quite beautiful, including the music – the kitsch factor is high, though. Kagaya also added narration of passages of the original story, but did not aim to retell the whole story, encouraging viewers to read the original instead.

Shōji Kawamori Peculiar Biography

Shōji Kawamori of Macross fame directed the 1996 movie Spring and Chaos (イーハトーブ幻想 Kenjiの春), produced by TV Iwate, the local television station of Miyazawa’s home prefecture. Kawamori also decided to portray the characters as cats, but this is not an adaption of a story, but a biographic take on Miyazawa’s life as a teacher, writer and farmer.

The one-hour movie portrays Miyazawa as a rather eccentric teacher and references some of his work, including Miyazawa’s Hoshimeguri no Uta song already used by Takahata. In addition to traditional cel animation, the movie has a couple of very interesting and experimental sequences that use beautiful, abstract crayon-styled animation to portray dreamlike sequences. These sequences are absolutely outstanding.

While people who don’t know anything about Miyazawa may be puzzled by this movie, I still think its message and atmosphere can be appreciated regardless of background knowledge. It is a competent retelling of Miyazawa’s grown-up life that covers topics such as his idealism, the death of his sister and his wish to become a farmer. Very peculiar indeed, but definitely worth a watch!

Kazuo Oga’s Solo Effort on Taneyamagahara at Ghibli

Ghibli Background Artist and Art Director Kazuo Oga adapted Miyazawa’s Night on Taneyamagahara at Studio Ghibli in 2006 – mostly all by himself. Oga is credited for direction, drawing all the key frames and “dramatization”. And it shows: This is not a typical animated movie, but rather a collection of stills with added narration. But these stills are beautiful! The story borrows the setting of Taneyamagahara, but the events are anime-original. I personally think it captures the appeal of Miyazawa’s story perfectly and absolutely does it justice. The narration is also quite excellent and pays a lot of attention to details – for example, the local Iwate dialect is used. Give it a try if you want to experience one of Miyazawa’s mysterious, yet oddly calming stories about nature.

(Screenshots from AniSearch)

Last But Not Least…

It may not stand out as much as the other works mentioned here, but my personal favorite of all Miyazawa adaptions is the 2016 version of Matasaburō of the Wind – a 25-minute short movie made as part of a subsidized training project for young animators, called Anime Mirai (now: Anime Tamago). The character designs are cute, the colors very appealing and it captures the calming yet mysterious nature I love so much about Miyazawa’s works. You can really feel the wind while watching!

These are by far not all adaptions, but from the ones I have seen, I consider them the most interesting.

Influenced Works

To conclude this article, I would like to name a few cases of other anime or manga works referencing or being influenced by Miyazawa’s works, first and foremost Night on the Galactic Railroad.

– As mentioned above, Leiji Matsumoto’s Galaxy Express 999 and The Galaxy Railways directly pay tribute to Night on the Galactic Railroad.

– In the 2013 post-war movie Giovanni’s Island (big recommendation), the protagonists are nicknamed after the protagonists in Night on the Galactic Railroad, and in a pivotal moment in the the second half, the galaxy train appears in a dreamlike sequence.

– Kunihiko Ikuhara’s Mawaru Penguindrum heavily references several elements of Night on the Galactic Railroad, including to Scorpion’s Fire.

– Both Bungaku Shōjo and Hanbun no Tsuki ga Noboru Sora reference Night on the Galactic Railroad several times.

– Hayao Miyazaki mentioned in an interview that that he always imagined the cat in Judge Wildcat and the Acorns as bigger-than-human as a child – a reason why Totoro is so big.

– In Takahata’s Pom Poko, two of Miyazawa’s songs are used as background music (I already mentioned the Hoshimeguri no Uta – the other one is called Spring Joy and seems to originate from Matasaburō of the Wind, from what I read on a Japanese blog).

– Jonathan Clements mentions Keiichi Hara’s Colorful and Birthday Wonderland movies also received inspiration from Miyazawa’s works.

– The song Hoshimeguri no Uta composed by Miyazawa himself is not only used in adaptions of his works, but also in Wish Upon the Pleiades (Gainax, 2015), Planetarian: The Reverie of a Little Planet (David Production, 2016), Baja’s Studio (Kyōto Animation, 2018).

Links

Notes on Galaxy Express 999

The Trouble with Budori Gusuco

Here I also found messages from various notable Japanese personalities, including the late Ghibli director Isao Takahata, producer Toshio Suzuki, composer Joe Hisaishi, In This Corner of the World director Sunao Katabuchi, mangaka Fumiyo Kōno, composer kotringo. I was amazed how many of these names were familiar to me.

Here I also found messages from various notable Japanese personalities, including the late Ghibli director Isao Takahata, producer Toshio Suzuki, composer Joe Hisaishi, In This Corner of the World director Sunao Katabuchi, mangaka Fumiyo Kōno, composer kotringo. I was amazed how many of these names were familiar to me.

Miyazawa’s most famous work is without doubt Night on the Galactic Railroad, a story about two boys, Giovanni and Campanella, who travel through the galaxy in a train before their inevitable parting. The story begins at Tanabata, the Star Festival in July. Giovanni boards a train that magically appears when he climbs a hill alone at night and meets his best friend, Campanella, there. What he does not know yet is that Campanella had fallen into a river that night, losing his live. The mysterious train takes them on a journey through the galaxy. The two boys witness all kinds of wondrous phenomenons, see beautiful places and meet bizarre people. They talk about their loved ones and the true meaning of happiness. But Giovanni is not dead, so he has to return to Earth in the end, while Campanella continues his journey into the next world.

Miyazawa’s most famous work is without doubt Night on the Galactic Railroad, a story about two boys, Giovanni and Campanella, who travel through the galaxy in a train before their inevitable parting. The story begins at Tanabata, the Star Festival in July. Giovanni boards a train that magically appears when he climbs a hill alone at night and meets his best friend, Campanella, there. What he does not know yet is that Campanella had fallen into a river that night, losing his live. The mysterious train takes them on a journey through the galaxy. The two boys witness all kinds of wondrous phenomenons, see beautiful places and meet bizarre people. They talk about their loved ones and the true meaning of happiness. But Giovanni is not dead, so he has to return to Earth in the end, while Campanella continues his journey into the next world.

urthermore, I found the following English picture books of Miyazawa works in the souvenir shop of the Kenji Miyazawa Memorial Museum:

urthermore, I found the following English picture books of Miyazawa works in the souvenir shop of the Kenji Miyazawa Memorial Museum: